Active SLAM

1. Introduction

Localization of a robot when the map of the environment is known is a trivial job. But in scenarios where one is unaware of the environment, it is impossible to localise the robot using traditional localization techniques such as Monte Carlo Localization or using Particle Filters. To address such situations, Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) algorithms are being developed over the years. Basically, SLAM is a problem of constructing and updating the map of an unknown environment while simultaneously allowing the robot to localise itself in the built map. There has been a lot of development in this field and some of the SLAM Algorithms are EKF-SLAM, GraphSLAM, ORB-SLAM, RGB-D SLAM etc. Though there is an advancement in the SLAM algorithms, there are still a lot of scenarios where SLAM fails. One strategy to implement for the betterment of performance is to leverage the robot’s motion to improve the localization and mapping. Active SLAM is formulated as the problem of controlling a robot's motion to minimize the uncertainty of its map representation and localization [8].

Active SLAM can also be seen as adding the task of optimal trajectory planning to the SLAM task. This integration allows a mobile robot to perform tasks such as autonomous environment exploration.

2. Applications

Exploring an unknown environment using a mobile robot has been a problem to solve for decades [1]. The applications extend to reconnaissance, rescue missions, cleaning a room, mowing a lawn, etc. Scenarios like these often don’t come with a priori map to work with for the robot. This problem is much harder to solve because most environments are complex, highly dynamic with lots of unknown uncertainties. Moreover, the robot has only access to a limited set of observations because of constraints on motors, limited field of view and noisy measurements from the sensors. In cases where the robot is operating indoors, the GPS sensor won’t be of much use, resulting in no absolute localisation service for the robot. Thus, estimation of robot pose and generating a map with time constraints become an essential and integral part of the robot’s decision making capability [2].

In ideal situations, a robot must take the least amount of time to explore an unknown map and generate a model of it. To achieve this, the robot has to take optimal decisions in each stage of exploration and move to the next area, which provides maximum information gain. It results in an exploitation and exploration decision making problem. For a robot to choose the best action, out of all the available actions, it has to generate utility by evaluating all the available actions before deciding one. This evaluation process is computationally intensive, and this intensity keeps on increasing with the increase in the unknown space [3]. People followed different approaches to sort this problem out. One such technique involves using multiple cooperating robots to explore the unknown environment. Using a team of multiple robots has its advantages. A team of robots can complete a given task much faster than a single robot [4]. Another significant advantage of using multiple robots is that the information stream from different robots can be merged to provide an optimal estimate of the information. But using multiple robots has its disadvantages. There might be interference between the sensors from different robots, and also there can be a cap on the communication range between these robots. By considering both the utility per action and the cost associated with that action, different robots in the unknown map will be able to select the right action at any given point of time.

Underwater robotics applications related to science, industrial or safety are mostly conducted in complex environments where the map of the area is not readily available. So, in most cases, these type of operations are generally carried out by a diver or a remote-controlled robot. To autonomously operate in such scenarios, the robot must have capabilities to map an underwater area, localise itself in it and plan its next course of action [5]. Several methods have solved this problem for robots operating in indoor and outdoor environments where some sort of mapping sensor accurately optimal view planning for objects or scene reconstruction. But, underwater systems do not have an accurate positioning system, poor visibility and low reliability of communications. All these inaccuracies lead to a gradual drift of the robot’s position to the actual position of the robot. Active SLAM helps the robot to decide a series of actions that leads to mapping the environment as efficiently as possible. In [6], the robot starts by moving to a viewpoint and senses the environment using a mapping sensor. This data is then used in a pose graph algorithm to correct the robot’s pose and the position of the previous viewpoints. The world is represented by a tree with the data gathered from each viewpoint. The robot then chooses the next best viewpoint to explore from a set of candidates from this tree representing the world. The candidate which provides the best utility is selected, and the robot chooses to explore that viewpoint. This process continues until a termination criterion is met.

3. Definition

Mathematical formulation of SLAM:

In SLAM, both the robot and the landmark's locations are estimated simultaneously when it explores the unknown environment. The ground truth information of where the robot and the landmarks are is always unknown to the robot. The observations done are noisy in most cases, and it tries to give an estimate to the robot about its current location and the landmark's location [7].

In the following equation, \(x_{k}\), denotes the location of the robot at time k. Hence, for a robot traversing a path, from the time it started till time k, can be given as,

\[X_{k} = {x_{0}, x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3} . . . . , x_{k}\]The relative motion of the robot between two-time steps k and k - 1, can be given by,

\[U_{k} = {u_{0}, u_{1}, u_{2}, u_{3} . . . . , u_{k}\]The relative motion \(U_{k}\) appears to be only a function of Odometry values. In real-world applications, the odometry readings suffer quite a lot because of wheel slippage and uneven surfaces. This lack of precision with the odometry readings leads to inaccurate localization. Hence, continuous reading from other sensors is required for precise localization. The readings from different sensors at every time step are defined as,

\[Z_{k} = {z_{0}, z_{1}, z_{2}, z_{3} . . . . , z_{k}\]SLAM uses a probabilistic distribution approach over the state of the robot to predict its current location and landmark location from the estimated map. This probability distribution can be given as,

\[P(x_{k}, m | Z_{k}, U_{k})\]The motion model and observation models are required which establishes a relationship the robot position \({x_{k}}\), the odometry \({u_{k}}\) and the sensory measurements \({z_{k}}\). The observation model and the motion model are given respectively as,

\[P(x_{k}, m | x_{k-1}, u_{k})\] \[P(z_{k} | x_{k}, m)\]The measurement model gives the robot the information about where the landmarks are, the current robot heading and the unique identifiers for every landmark. The measurement model can be given as,

\(P(z_{k} | x_{k}, m)\) which is approximately equal to, \(N(h(x_{k}, m), Q_{k})\)

where,

\(h(x_{k}, m)\) tells us about sensory operations

N is a normal distribution

\(Q_{k}\) is noise covariance

h is a function that outputs the estimated measurement of the current pose of the robot

The motion model can be derived by applying normal distribution and it can be defined as,

\(P(x_{k} | x_{k-1}, u_{k}) = N(g(x_{k-1}, u_{k}), R_{k})\)

where,

\(g(x_{k-1}, u_{k})\) is a kinematic function

\(R_{k}\) is noise covariance

g returns the new position \(x_{k}\)

The estimate of the robot’s position and the landmarks position at time instant \((k - 1)\) will get updated when the robot moves to a new position at time instant \(k\) based on the new estimate. This process continues until the robot completes exploring the unknown environment.

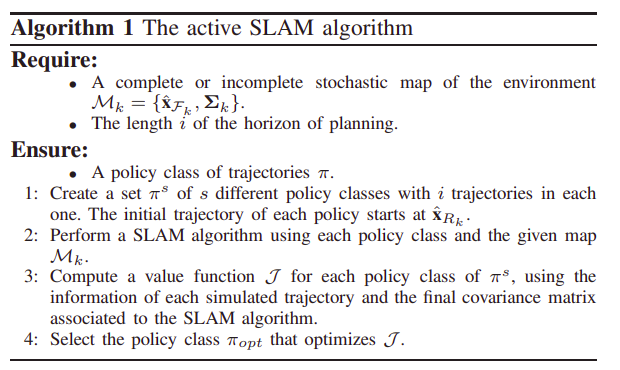

Algorithm of Active SLAM:

In general, the SLAM problem does not address the trajectory planning of a robot. Usually, the trajectories are chosen randomly or beforehand. However, it is known that the trajectories that the robot will follow are important for the following reasons:

- For a rapid convergence of the uncertainty of a SLAM algorithm

- For increasing the area that the robot has explored

- To improve the possibility of fulfilling certain specific tasks

This integration of the trajectory planning task into the SLAM problem is referred to as Active SLAM problem. The general idea of Active SLAM is summarized in the following algorithm [12]:

4. Active SLAM is a decision making problem

Active SLAM's performance will be good if the robot motions are appropriate as in the robot should move in a path where the localization and map uncertainities are very less. So Active SLAM is a decision making problem i.e a decision needs to be made on how the robot should explore the environemnt before going to the planning task.

The concept of Active SLAM was introduced mainly to solve the exploration problem in an unknown environment. It is proved by Thrun in [13] that solving the exploration-exploitation dilemma is more efficent than pure exploitation or random exploration. It is basically finding a balance between visiting new places (exploration) and reducing the uncertainty by re-visiting known areas (exploitation). There are several general frameworks for decision making that can be used as backbone for exploration-exploitation decisions, some of which will be discussed in next section.

5. Brief description of variants

Theory of Optimal Experimental Design (TOED):

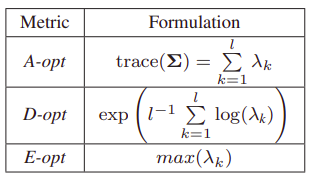

One of the frameworks to solve the Active SLAM problem is by the use of Theory of Optimal Experimental Design (TOED), which decides the actions to be carried out for effective robot motion based on the predicted map uncertainty. These uncertainty metrics aim at determining whether or not the uncertainty represented by a covariance matrix, Σ, is large or small. Mathematically, an uncertainty criterion has to define a function φ that maps a covariance matrix to a scalar. This function should ideally be isotonic (preserving the order), positive homogeneous and concave. The most commonly used uncertainty criteria (covariance matrix Σ of size l × l and having eigenvalues λl) are:

- A-optimality criterion (A-opt): This criterion targets the minimization of the variance.

- D-optimality criterion (D-opt): This criterion aims at capturing the full dimension of the covariance matrix.

- E-optimality criterion (E-opt): This criterion intends to minimize the maximum eigenvalue of the covariance matrix Σ.

The formulae to calculate the three mentioned criteria are given below [14].

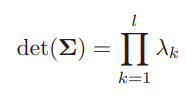

According to the Theory of Optimal Experimental Design, D-opt is the best uncertainty criterion, but for solving active SLAM, it was believed previously that the D-opt does not produce a meaningful metric as they were considering the formula shown below for computing D-opt. By using this formula, the value gets stuck at zero.

Later, it was proved that the D-opt uncertainty criteria can be used for solving active SLAM by writing the formula for it as shown in the table. It’s proved in [12] that D-opt performs comparably to A-opt metric as popularized in [15], [16] and [17].

Information Theoretic Approaches:

Solutions have been developed over years to solve the active SLAM problem using the information gain in the decision-making process. There are many research works which focus on the Occupancy Grid (OG) maps to compute the information gain while exploring the map [18]. This process of using OG maps has a lot of disadvantages and results in poor robustness and scalability. Consider the scenarios where there is significant drift in the estimated robot's pose. This uncertainty is not included in the Occupancy Grid maps. To improve the performance, recent works are focussed on feature maps. In feature based representation, features are maintained in the graph resulting in a good layout of the map. However, solving an active SLAM problem with feature maps is difficult as they do not offer any information on obstacles. Anyway, research has continued in this field and there are solutions for the active SLAM problem which use feature based representations without any underlying OG maps. In [19], they have developed an Information-based Active SLAM using Topological Feature Graphs.

Control Theoretic Approaches:

As mentioned earlier, Active SLAM involves the planning of efficient paths for an autonomous robot to traverse while doing the SLAM process. It can also be formulated as an optimal trajectory planning problem. Along with the consideration of uncertainties of the sensor measurements, robot and map; it is necessary to account for the dynamic and motion constraints in the planning process. Local planning algorithms like Model Predictive Control (MPC) are suitable for dynamic environments. In many works MPC has been successful for solving the SPLAM (Simultaneous Planning Localization and Mapping) problem. However, it's observed that MPC is incapable of perceiving beyond the set planning horizon. To improve the performance, we can extend the planning horizon but that will exponentially increase the computational costs. This Receding horizon control (a.k.a MPC) also fails to proactively explore as it is not capable of predicting new features. To address this without increasing the costs, an interesting technique has been proposed in [20] that uses an attractor combined with local planning algorithms like MPC in optimal trajectory planning. The attractor enables global information and incorporates high level tasks in the planning process. It is observed that this solution which uses attractor along with local planning strategies perform much better than systems with local planning alone.

Partially Observable Markov Decision Process:

The exploration task can be thought of as choosing the optimal actions in partially observable stochastic domains. Previously, in the Artificial Intelligence literature, a deterministic approach has been introduced to address this problem which suggests adding the pre-acquired knowledge to traditional planning systems. But for stochastic environments, this approach will not give good results. So, one way to go about solving the Active SLAM or planning under uncertainty problem is to formulate it as a POMDP (Partially Observable Markov Decision Process). In the deterministic approach, the plans are considered as a sequence of actions which may rarely execute as expected. But in solving a POMDP, we take them as mappings from situations to actions that specify the robot’s behaviour. The optimal performance gained by solving a POMDP is similar to what we achieve with a “value for information” approach. However POMDP is more complex as the robot chooses between actions based on the amount of information that’s provided, the amount of reward they produce, and how they change the state of the world [21]. One disadvantage with the POMDP approach is that they are computationally intractable. So, in recent times, approximate but tractable solutions have been provided like the Bayesian Optimization [2] or efficient Gaussian beliefs propagation to solve the active SLAM problem [22].

6. Discussion of open research questions

Active SLAM is still really far away from being used with real applications for everyday use [8]. Some of the problems that require attention are mentioned below,

Fast and reliable prediction of future states:

In the process of evaluating the next best possible action, the robot might take, a series of evaluation of all the possible actions are considered. These actions are evaluated based on its contributions to aid in the accurate localisation of the robot and to minimise the effort in mapping the environment. From a given position, the robot might have the freedom to perform numerous actions depending on its action set. Thus, the ability to foresee the effect of action with minimum latency becomes essential in the decision-making process [9]. Loop closing is necessary for the robot to reduce uncertainty about its localisation and mapping accuracy. Efficient methods for foreseeing the future effects of performing an action and the effect of loop closing are still under research. Though the process of predicting the future impact of an action is computationally expensive, there are recent advancements by using spectral techniques and deep learning.

When to stop doing active SLAM?

Active SLAM is computationally expensive because of the whole decision-making process happening under the hood. In such cases, there should be a termination criterion that tells the robot to stop doing active SLAM and continue its exploration with passive SLAM. The process of switching back to passive SLAM from active SLAM is mainly done to allocate resources to other tasks that might require attention [10]. This termination criterion is essential because, after some point, too much information will only lead to contradictory results and might end up in non-recoverable states due to several wrong loop closures.

Mathematical guarantees:

Solving the problem of active SLAM exactly is a difficult task. We need more mathematical guarantees and near-optimal policies which will provide more understanding of what to expect from the process. One such effort involved using submodularity in active sensor placements where approximation algorithms with performance bounds were used [11].

7. Conclusion

With the advancements of new technologies including new sensors, algorithms and powerful computing platforms, the problem of SLAM has seen tremendous progress over the past 40 years. Some important questions have been answered, and new questions have risen along the way. Even with recent advancements in active SLAM, the latency problem with foreseeing the effect of an action to evaluate and choose the best action is still a problem to be solved. So, it ideally raises a question of when to use active SLAM and when not to use it. SLAM and related techniques have found applications in a lot of real-world applications where solutions such as GPS is not available or highly inaccurate.

Based on the application, the robot can use different variants of SLAM formulation. A topological map will provide us with information that will let us know if the given goal point can be reached by the robot or not while limiting the robot to perform planning and navigational operations. While a globally consistent map will allow the robot to perform path planning and low-level control, but it will be computationally intensive.

An active SLAM approach can only be chosen with complete information about the robot, the environment where it’s going to operate, the performance metrics and the computational power of the system onboard. To achieve a robust algorithm and method for autonomous robots to perform efficiently and be fail-safe, more research needs to be done, and a lot of problems require attention.

8. References

1. C. Cadena, L. Carlone, H. Carrillo, Y. Latif, J. Neira, I. D. Reid, and J. J. Leonard. Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), Workshop “The problem of mobile sensors: Setting future goals and indicators of progress for SLAM”. http://ylatif.github.io/movingsensors/, Google Plus Community: https://plus.google.com/communities/102832228492942322585, June 2015.

2. R. Martinez-Cantin, N. de Freitas, E. Brochu, J. Castellanos, and A. Doucet. A Bayesian Exploration-exploitation Approach for Optimal Online Sensing and Planning with a Visually Guided Mobile Robot. Autonomous Robots (AR), 27(2):93–103, 2009.

3. Cindy Leung, Shoudong Huang, and Gamini Dissanayake. Active slam in structured environments. In ICRA, pages 1898–1903. IEEE, 2008.

4. M. Kontitsis, E. Theodorou and E. Todorov, "Multi-robot active SLAM with relative entropy optimization", 2013 American Control Conference, 2013. Available: 10.1109/acc.2013.6580252 [Accessed 7 October 2020].

5. F. Hidalgo and T. Braunl, "Review of underwater SLAM techniques", 2015 6th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications (ICARA), 2015. Available: 10.1109/icara.2015.7081165 [Accessed 7 October 2020].

6. N. Palomeras, M. Carreras and J. Andrade-Cetto, "Active SLAM for Autonomous Underwater Exploration", Remote Sensing, vol. 11, no. 23, p. 2827, 2019. Available: 10.3390/rs11232827 [Accessed 7 October 2020].

7. A. Khairuddin, M. Talib and H. Haron, "Review on simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM)", 2015 IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE), 2015. Available: 10.1109/iccsce.2015.7482163 [Accessed 7 October 2020].

8. C. Cadena et al., "Past, Present, and Future of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: Toward the Robust-Perception Age", IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 1309-1332, 2016. Available: 10.1109/tro.2016.2624754 [Accessed 7 October 2020].

9. V. Indelman, L. Carlone, and F. Dellaert. Planning in the Continuous Domain: a Generalized Belief Space Approach for Autonomous Navigation in Unknown Environments. The International Journal of Robotics Research (IJRR), 34(7):849–882, 2015.

10. H. Carrillo, O. Birbach, H. Taubig, B. Bauml, U. Frese, and J. A. Castellanos. On Task-oriented Criteria for Configurations Selection in Robot Calibration. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pages 3653–3659. IEEE, 2013

11. D. Golovin and A. Krause. Adaptive Submodularity: Theory and Applications in Active Learning and Stochastic Optimization. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 42(1):427–486, 2011.

12. H. Carrillo, I. Reid, and J. A. Castellanos. On the Comparison of Uncertainty Criteria for Active SLAM. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pages 2080–2087. IEEE, 2012.

13. S. Thrun. Exploration in Active Learning. In M. A. Arbib, editor, Handbook of Brain Science and Neural Networks, pages 381–384. MIT Press, 1995.

14. H. Carrillo, Y. Latif, J. Neira, and J. A. Castellanos. Fast Minimum Uncertainty Search on a Graph Map Representation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), pages 2504–2511. IEEE, 2012.

15. L. Mihaylova, T. Lefebvre, H. Bruyninckx, K. Gadeyne, and J. De Schutter, “A Comparison of Decision Making Criteria and Optimization Methods for Active Robotic Sensing,” in Numerical Methods and Applications, ser. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer Berlin/ Heidelberg, 2003, vol. 2542, pp. 316–324.

16. R. Sim and N. Roy, “Global A-Optimal Robot Exploration in SLAM,” in IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation, Apr 2005, pp. 661 –666.

17. T. Lefebvre, H. Bruyninckx, and J. De Schutter, “Task Planning With Active Sensing For Autonomous Compliant Motion,” The International Journal of Robotics Research, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 61–81, 2005.

18. H. Carrillo, P. Dames, K. Kumar, and J. A. Castellanos. Autonomous Robotic Exploration Using Occupancy Grid Maps and Graph SLAM Based on Shannon and Rényi Entropy. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pages 487–494. IEEE, 2015.

19. B. Mu, M. Giamou, L. Paull, A. Agha-mohammadi, J. Leonard and J. How, "Information-based Active SLAM via topological feature graphs," 2016 IEEE 55th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Las Vegas, NV, 2016, pp. 5583-5590, doi: 10.1109/CDC.2016.7799127.

20. C. Leung, S. Huang, and G. Dissanayake. Active SLAM using Model Predictive Control and Attractor Based Exploration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), pages 5026–5031. IEEE, 2006.

21. L. P. Kaelbling, M. L. Littman, and A. R. Cassandra. Planning and acting in partially observable stochastic domains. Artificial Intelligence, 101(12):99–134, 1998.

22. S. Patil, G. Kahn, M. Laskey, J. Schulman, K. Goldberg, and P. Abbeel. Scaling up Gaussian Belief Space Planning Through Covariance-Free Trajectory Optimization and Automatic Differentiation. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Algorithmic Foundations of Robotics (WAFR), pages 515–533. Springer, 2015.